November 8th 2020

10:27 am - 'And they're off!'

For those of us in Europe, the 8th

of November is already upon us. At the time of writing it is 10:27 am, I am outside

Leeds in Yorkshire, UK, and just under half-an-hour ago, polling places in

Vermont opened for the 2022 Midterm General Elections in the US. Indeed, after

months of data assemblage and analysis, the midterms are here. As the elections

unfold, in between my lessons, I intend to blog about some of the electoral data that I have been analysing

over the past month or so. I will cover both those races for the US House of

Representatives and the US Senate. Sadly, this does mean that I will not be

looking at Gubernatorial elections today. Nonetheless, there is some great discussion

at Politico,

Fivethirtyeight

and 270ToWin,

amongst so many others, that I would direct the reader to if they want to know

more about the nation-wide gubernatorial elections. Over the course of the next

24 hours (probably more like 72 hours!) I am going to try and keep blog posts

short, adding to this one page as we go through the day. So,

I have already analysed and made my

predictions for turnout by looking at historical turnout data, using it as a

guide to cut through the fog of speculation. which you will be able to find on

the poLit blog HERE.

In this piece, following an analysis of past turnout data, I argued reluctantly

that we can statistically assume that turnout will fall between 42-48%, at

least if this midterm election doesn’t buck every trend and statistical

likelihood. Nonetheless, as I said here, don’t hold me to this, as 2018

returned a 50% turnout after a contemporary low in 2014, amidst a 5 in 10

billion probability using turnout data from 1986-2014.[1] So, this ‘prediction’

could simply turn out to be balderdash. Nonetheless, if we are using the data

to guide our analysis, its what we should expect. Figure 1 below details Midterm

General Election turnout from 1986 to 2018.

Figure 1: United States Midterm General Election Turnout Rate (%) (1986-2018)

I would like to start by broadly looking

at why these Midterm general elections are so important. Chiefly, beyond the

specific policy that some would like or dislike to see implemented by any

particular party holding the machinery of congressional government, as Midterms

so often do, this election could result in greater divided government. Simply put,

divided government is a situation in which no one party holds all three branches

of government; these being (1) the executive (President and Cabinet), (2) the

Legislative (Congress), and (3) the Judicial (The Supreme Court).

As it stands, we already have a division

between the ideological leanings of the Executive – held currently by Joe Biden,

who is a Democrat – and the Judiciary – which currently holds 6 Conservative and

just 3 Liberal justices, many of whom are activist judges.[2] Already, in the last year

alone, we have seen a number of Supreme Court decisions that are at odds with

the ideological preferences of the White House. For instance, to name a few

cases, the Court has: (a) removed the constitutional protection of abortion

rights, (b) curtailed the ability of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

to regulate aspects of the Energy Sector, (c) ruled that the exclusion of

religious schools from a state tuition programmes is a violation of the free

exercise of religion, and (d) declared that strict limitations requiring a

person to show a need for self-protection in order to carry firearms in public

violates the second amendment.[3] Thus, in many ways, the US

is already experiencing divided government ideologically, over constitutional

protections.

Nonetheless, a divided government of the

kind most often experienced – and perhaps most immediately felt - is the division

between the legislature and executive, between congress and president. In all

honesty, divided government is not an unusual affair. Of the twenty-two years in

the twenty-first century, ten of them have been collectively spent under

divided government; with the greatest share over the last three-quarters of the

Obama administration (2011-2017). Some, indeed idealistically perhaps, consider

this a positive attribution to hold in any given political system, as divided government

should ‘temper’ the worst extremes of partisanship and force bipartisan

compromise; a particularly Madisonian notion.[4] I can think of no better demonstration

of this perspective than that eschewed out on Twitter yesterday by its

new owner, Elon Musk. Figure 2 below shows Musk’s tweet and the idealistic

optimism that is thought to be achieved through a divided government, inciting

the independent voter to support the Republican party to these ends.

Figure 2: Tweet by Elon Musk declaring his

support for a divided government.[5]

Of course, a number of Scholars contend

that a divided government is not a limit on the efficacy of government,

and such a Madisonian notion is equally not idealism. In his ‘Divided We

Govern’, the renowned political scientist David Mayhew presented this

thesis. Mayhew found that there was little difference concerning the

environment of policy making between divided and unified governments, i.e., the

volume of significant laws passed in periods of divided government did not

considerably differ from periods of unified government.[6] This being said, perhaps

Mayhew’s argument errs in locating nuance. Mayhew chooses a simple measure in

order to conduct his research – the supply of legislation – and hence neglects

to include into his design a measure that concentrates on the demand for

such legislation.[7]

The question remains therefore, does divided government stagnate legislative

action that is normatively willed by the electorate, or does it simply make

executive dominance of the political edifice more complex to achieve?

Significantly, since Mayhew’s study, a host

of research has been undertaken negating such a claim. In fact, divided government has often led to periods of

enmity between the branches, whereby constitutionally provided for checks and

balances are utilised like wild-cards in a game of UNO. Such enmity manifests

as a gridlocking of the system, the only casualty of which is the passage of important

legislation that is either discounted by the Legislature because it has come

from the Executive, or vetoed and fought by the Executive because of its passage

through congress. In the words of one particular comprehensive study:

“Does divided government have a

significant influence on the passage of important legislation? It does.

Presidents oppose significant legislation more often under divided government,

and much more seriously considered, important legislation fails to pass under

divided government than under unified government. Furthermore, the odds of such

legislation failing to pass are considerably greater under divided government.”[8]

Thus, as it is expected that

the Republicans will take control of the House of Representatives, we should

expect there to be a reduction in the number of significant pieces of

legislation passed at the federal level, at least until the rock or hard place

shifts.

Equally, ideological partisanship

in Congress is at a record high. This will only stoke the divisive activity

that divided government will cause. Indeed, by measuring ideological shifts in

congressional politicians since 1972, we can see that both parties in both chambers

of Congress have become more polarised. According to data provided by Pew

Research Centre, using their own scale of measurement, since 1972, in the House

of Representatives the Republicans have moved +0.25 to the right and Democrats

-0.07 to the left; whereas this is +0.28 to the right for the Republicans and

-0.06 to the left in the Senate.[9] Figure 3 lays this out

below.

Figure 3: Average Ideology of Members, by Congress

(1972-2022).

The country is more divided

than ever, and this is seen no more so than in congress. With such a move to

the right in the last four years, since 2018 and the Democrat’s seizure of the

House, the events of January 6th 2021, will divided government paralyse

legislative procedure even more so than expected? Paralysis is expected to some

degree, but will such a paralysis plus partisanship create a new kind of divided

government? Perhaps one devoid of bipartisanship altogether? Even before the

sun on election-day had risen, although ‘refusing’ to use checks and balances ‘to

play politics’, Kevin McCarthy – the leader

of the GOP in the House, and more than likely the next Leader of the House – insinuated

that ‘accountability’ perhaps in the form of impeachment is on the cards, alongside

a reversal of some democrat-led House decisions over the past few years.[10] This is why this election

is so significant. Not necessarily due to the legislation that may or may not

be passed, but due to the kind of governance it could very well usher in and be

the initial electoral marker of.

Stay tuned.

10:18 pm - 'Oh, Those Singe-Minded Seekers of Re-election!'

One of the greatest critiques of

term-length for Congressional representatives came from David Mayhew. In his

long essay ‘Congress: The Electoral Connection’, Mayhew discuses the

extent to which the representative-constituency link between congressional

representatives and constituents is determined by these term lengths. As

representatives of the house are up for re-election every other year, they

never leave the campaign trail; even after winning another term the potential

of losing one’s position is always somewhere on the horizon, just 24 months in

the distance. Alongside this, Senators are afforded a healthy six years in

which to make changes for their state-wide constituents. In both cases, if a

representative does not deliver results with the time they have, they will be

elected out of office. Mayhew argued that this has led to a milieu in which

congressional representatives are ‘Single-Minded Seekers of Re-election’, where

a certain self-interestedness to secure good electoral prospects occupies the

rationale behind every action that a congressional representative makes;

seeking to lay a claim to any legislative activity, pay-offs, initiatives,

policies, and especially funds towards popular projects (known as

‘pork-barrelling’) that they can.[11]

One of the most interesting things about

US Congressional Politics is that every two years we get to see whether or not the

efforts of these ‘Single-Minded Seekers of Re-election’ do indeed pay off - or

not. It’s time to turn attention to exactly this and centre focus on the US

House of Representatives.

Prior to this election, the make-up of

the US House of Representatives stands at:

- 220

Democrats

- 212

Republicans

- 3

Vacant Seats

As there are a total of 435 seats in the

US House of Representatives, we need to remember that the magic number here –

the number to form a majority – is 218. As we can see from Figure 4 below, this

means that the Republicans only require a net gain of 5 seats on the 2020 election

in order to take the lower house of Congress. Even if we just look at the

twenty-first century alone, what we can see is that the party holding the

executive branch tends to lose seats at midterms. Indeed, if we look at the

seat changes just in the twenty-first century alone, the average seat loss in

the US House of Representatives for the party holding the executive branch is

-28.2 (the loss of 28.2 seats). If we place this under a normal distribution

curve, the likelihood that the Democrats will lose those five seats returns a

probability of 83 in 100 – just from this data alone, without even

considering polling.[12] Indeed, if we look at the

pollsters, their estimation is somewhat similar. In the case of FiveThirtyEight,

they are estimating that the probability the Republicans will take the House

sits at 84 in 100.[13]

Figure 4: Number of Seats Won by the Republican

and Democratic Parties in Elections to The US House of Representatives

(1984-2020)[14]

This aside, as Congresspersons are, in

Mayhew’s terms, ‘Single-Minded-Seekers of Re-election’, the incumbency rate

also quite high. Broadly speaking, only a small percentage of seats actually

change hands as so many incumbents go on to win their re-election. If we look

at Figure 5, we can see that the average historic rate of incumbency since 2000

sits at 93.91%. Thus, if this election were to return this average incumbency

rate, 26-27 representatives would lose their seat. In this period, the highest rate

of re-election was in 2000 or 2004, where 97.8% of representatives were re-elected.

Using this data, the probability that this election would exceed this high-point

is but 14 in 100, over one standard deviation from the mean of the twenty-first

century thus far.[15]

The lowest in the same period was in 2010, wherein the Democrats lost 64 seats,

and so overall returned an incumbency rate of 85.4%. That this election’s incumbency

rate will indeed drop below this, seeing a high number of incumbents ousted, returns

a 0.92% probability – almost a 1 in 100 probability.[16] Lastly, the likelihood

that more incumbents will lose their seats than in the last election, returning

a 94.7% re-election rate, is around 59 in 100.[17] Hence, statistical probability

indicates that more than 23-24 incumbents will be ousted at this election.

Figure 5: US House of Representatives Re-Election Rates (%) (2000-2020)[18]

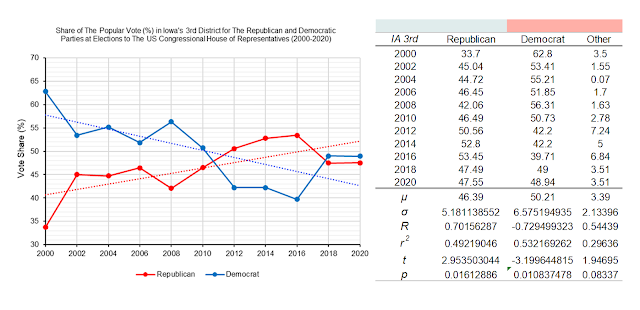

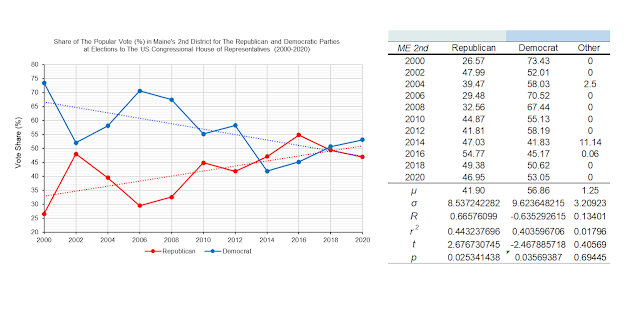

Now this has been discussed and we know that

the likelihood of the House flipping to the Republicans is high and that we

should expect more than a handful of incumbents to lose their seats, what does

the historical vote share of the parties in the US House of Representatives

tell us? Are there any trends over time?

The results are coming in as I type, the night has just begun. Ok, before we start talking about which races

could flip the House, and which ones are broadly interesting to keep an eye on,

lets talk history. First, we will look at how parties have historically faired in

terms of seats won. Following this, vote share will take centre stage. In both

cases we will first begin with the long-term perspective, before honing in on

the data from the twenty-first century alone.

If we return to Figure 4, we can see the

spread of seats won by party at General Elections for the US House of

Representatives from 1984-2020. This gives us a fairly long-term view of how the

two parties have performed at elections. We can see that in this period the

average amount of seats the Republicans win (to the nearest whole) is 210, and

the Democrats 224 respectively. What is significant to highlight about this is

that since 1984 we can see two rather strong inverse correlations with time. In

the first instance, as time passes the Republicans’ share of the seats in the

House grows with time - moderately.[19] The converse can be said

for the Democrats, for whom their share of the seats in the House has regressed

in correlation with time – moderately also – although not quite to the same

degree as the Republican’s seat share has grown.[20] Naturally, the US holds a

two-party system, and so where there are correlations, the parties tend to

mirror one another.

Consequently, the same could be said for

their highest and lowest returns. For highs and lows in this period, the two

years to recall are 1990 and 2014. In 1990, the Democrats achieved their highest

return of the period, winning 267 seats, whilst the Republicans sat 100 seats

behind the Democrats at 167. Over twenty years later, however, the turns had

tabled. In 2014, the Republicans won 247 seats and the Democrats 188,

respectively. This allows us some context for what to expect, given a longer-term

view.

If we narrow this temporal aperture a

little, we can see that a shift takes place. Looking at Figure 6 below,

detailing seats-won in the House between 2000-2020, in fact the narrative almost

entirely shifts. Since 2000, the Republicans have won an average of 222 seats

(to the nearest whole) and the Democrats 213. Thus, in the twenty-first

century, we can say that the Republicans perform better than Democrats in the

race for the House, at least on average. This will be a factor that will hang

heavy over the Democrat’s capability to hold the House. Equally, Figure 6 clearly

details that those correlations we see over the longer-term simply dissipate. Neither

the Democrats nor the Republicans hold any significant correlation with time in

this period. In fact, the only significant correlation with time is that Independents

hold a negative regression with the passage of time in this era. Interestingly

however, if we use this data as a foundation, we can see that the Republicans would

be likely to achieve a majority (218 seats) 57 in 100 times.[21]

Figure 6: Number of Seats Won by the Republican

and Democratic Parties in Elections to The US House of Representatives (2000-2020)

Let’s turn our gaze to vote share now,

which will tell us how popular the parties were nationally at each election. Figure

7 details popular vote (%) for the Republican and Democrat Parties at elections

for the US House of Representatives from 2000-2020. Firstly, we can see that unlike

seat share in the same period, the Democrats hold the higher average. Between

2000 and 2020, the Democrat vote share for the US House sat at 48.37%, whereas

the Republican average fell just slightly below this, at 47.42%. Where are the

highs and where are the lows?

Figure 7: Popular Vote (%) of the Republican and

Democratic Parties in Elections to The US House of Representatives (2000-2020)

Much as in the case of seat share, a

good year for one party denotes a bad one for the other – as is the way with

two-party systems. Let’s begin with the Republicans. The GOP had its worst

House result, in terms of popular vote, in 2008 – the year that Obama is

elected President. Here, the Republicans took 42.38% of the vote. Just two

years later, at Obama’s first Midterm election, the Republicans bounced by 9

points to achieve a period high of 51.38%. The reverse holds for the Democrats.

The Democrats achieved their high in 2008 – a massive 52.93%, and with its

inverse parallel to the Republican party, two years later in 2010 the Democrats

dropped by 8.06 points to their period low of 44.87%.

I think it is important to mention that there

are no statistically significant correlations between partisan national vote share

for the House and time. In fact, perhaps it should be noted that there is

barely any correlation with time, let alone statistically significant

correlations. The Democrat vote share has a mild positive correlation with time

(where R = 0.29775) and the Republican popular vote has very slight

negative correlation (where R = -0.07085) but this is a verging plateau

at best – an empty can in the wind would struggle to roll down such a decline.

Finally, before we talk about some specific

seats that I think we should keep our eyes peeled to, let’s talk probabilities

using this data. There is a 2.35% chance that the Republicans will fall lower

than their 2008 basement-level vote share and a 7 in 100 likelihood that they

will exceed their 2010 high, far over one standard deviation from the mean. If

we work out the probability that the GOP vote share for elections to the House

will sit between these two poles in 2022 – between their highest and lowest of

the period – we see that this scenario occurs 89 times in 100.[22] Lastly, with this data in

mind, the Republicans have a 52.73% likelihood of increasing their share of the

vote from their 2020 result (47.23%). Nonetheless, given the trends

historically at midterms, this is likely more certain than not. However, it is

unlikely that they will surpass 50% of the total vote share, occurring only 17

times in 100.[23]

So, to be clear, statistically speaking, we should assume that the Republican

vote share will fall between 47-50%. This being said, past midterms have normally

swung the vote share over 50% for the winning party in the House – so either

the country is exceptionally polarised or such a trend will hold.

Lastly, lets talk about the Democrats.

The likelihood that the Democrats will exceed their 2008 high, from this data

alone without the context of midterms, returns under a 7 in 100 probability, not

far from 2 standard deviations from the mean.[24] The scenario that the

Democrats steal the popular vote, somehow, and gain 51% of the vote share

occurs only 19 in 100 times. More likely than the Republicans are in achieving this

milestone, but that is without the context of the Midterm. If we were to

wire-in this context, the probability of this occurring is far, far slimmer.

Indeed, overall, we should expect the

Republicans to outperform the Democrats on all of the measures we have just

discussed. As far as any prediction is concerned, thus far there are almost 35 House

seats that are exceptionally close - dare I even say ‘battleground’ districts.

If we remove these, I would say we can statistically predict that the

Republicans will get at least 210 seats, and the Democrats 190, respectively. Thus, the night may have just begun in the US, but the faint glow of a House of a rising red sun glints below the horizon.

Now, which seats should we be looking

at?

3:02 am - 'A Brief Moment to Remember The 2020 House Election Results'

Before I skip to laying out which races I think are significant to watch in the battle for control of the House, here is a brief reminder of the 2020 US House of Representatives results. These will be the figures that the outcome of this election will be measured against.

Figure 8: The Results of the 2020 Election to The US House of Representatives.

3:28 am - Where Should We Look?

The following is a list of House Races that I will be focussing on today as the results come in, for a number of reasons. Do be advised, however, a number of these districts have gone through a re-districting on multiple occasions. The colours indicate firstly the party of the incumbent, then the party I expect to win the seat - of which I could be wrong on every count. A light cream colour indicates that it is 'toss-up' between the parties and in some cases this may come with a lean, as in the case of the IL 14th, for instance. Thus, in no particular order...

Now that my discussion of the US House of Representatives is complete, we can now move on to The US Senate, the upper chamber of the bicameral congressional system. Before I discuss the Senate in any depth, before any one of those races I have isolated as being significant is called, I would like to lay out those seats I think are key races to this Senate race. Given that the Republicans only need a net gain of 1 seat to flip the Senate, there are a number of key battleground states that require our focus. All in all there are 10 that I think could decide this Senate election - 5 held by Republicans and 5 held by Democrats. In no particular order, they are:

As a new day dawns over the terraced

houses of Leeds, this will be the last addition to this Live thread on the US

2022 Midterms. I intend to write a piece discussing the outcome more succinctly.

As it stands now, almost all races are underway. The only institution I was

unable to cover thoroughly was the US Senate. I had previously uploaded to this

thread my predictions of key races alongside the raw graphic data, nonetheless

this came without any particular explanation. As tiredness and spectator fatigue

sets in, I would like to take a few moments to lay out what I intended to

discuss concerning the Senate – at least before I collapse into beauty sleep.

For the record, my prediction was that

after a handful of Senate seats were flipped - for both parties – the final

result would leave the Senate in Republican hands. My estimation was that the Republicans

would emerge from this election with 51 seats and the Democrats (and

Independents) with 49, implying a net gain for each party.

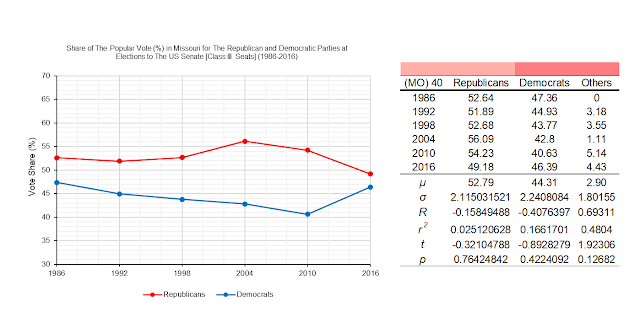

I was intending to focus on only the

third class of Senate seats that were up for election this November –

discussing the averages over the period of six election cycles (stretching back

to 1986) and the probabilities of change from this data. For the sake of

posterity, of these Class III seats alone and excluding the results of special elections,

the Democrats held the higher average vote share of 49.53% and the Republicans

46.01%. In relation to seat share, over the same period (1986-2016), the

Democrats averaged 49.67 seats and the Republicans 49.5 – a very slight

difference that illustrates just how tight races for the US Senate are on the

whole. That the Republicans will achieve more than 50% of the popular vote in

this US Senate Election, using the cycle of Class III seats only, holds just

over a 2% probability – over two standard deviations above the mean. Nonetheless,

that the GOP gains a single seat has a far higher probability, of almost 38 in

100. That the Democrats would achieve the same feat is not much higher, resting

at just 40 in 100 – and this is without the midterm context. None of this,

however, rallies against the probability that the Republicans will increase on

their 2016 vote share – a 96 in 100 chance – almost statistically bound to

occur.

There are no statistically significant correlations

with the passage of time in relation to either seat or vote share for either

party at elections for US Senate Class III seats, or the US Senate as a whole

in fact. This thus meant that in order to analyse the Senate race, an

increasingly granular focus would have been required.

In order to facilitate such a granular

focus, I then would have explained how I divided the 35 Senate seats up for

election into ‘seats of interest’, i.e., those that would be tight races; be

that as a result of thin margins at previous elections, contextual changes

internally to the state, or just the interest of those states like Georgia, the

incumbent of which, Raphael Warnock (D), has only been in the position for two

years. From here, of those states of interest, they were to be broken down by partisan

incumbency and then displayed individually with an emphasis on the counties

that had broadly changed their partisan voting preference from the previous

election, and so would be where the parties would be looking to either reverse

such a trend or entrench it. I chose to display these individual races in the

previous post, so to ensure my predictions were uploaded before a result was

called in any of them. Here are the graphics I would have used to explore all

of this:

Figure 9: Number of Seats Won by The Republican and Democratic

Parties in Elections to The US Senate - Class 3 (1986-2016)

Figure 10: Popular Vote (%) of Republican and

Democratic Parties in Elections to The US Senate - Class 3 (1986-2016)

Figure 11: US Senate Seats up for Election on

November 8th 2022

Figure 12: US Senate Seats of Interest up for

Election on November 8th 2022 Held by Democrat Incumbents

Figure 13: US Senate Seats of Interest up for Election on November 8th 2022 Held By Republican Incumbents

Sadly, given that I physically cannot intake any more caffeine, its time I hang up the calculator. Thus, the only thing I have left to say is thank you for sharing this Midterm Election Night with me. Check back in a couple of days, or maybe even a week, for my post-election analysis. Nonetheless, I look forward to seeing you in two years’ time when, judging by recent news, it will certainly be one that should Trump what we have come to call political theatre - for the second time in a decade. See you then - I look forward to it.

[19] R = 0.57218, p = 0.01047.

It may also be of interest to the reader to know that, unsurprisingly, there is

a strong correlation here with republican vote share, where R = 0.84598

and p = 0.000005.

[20] R = -0.56449, p = 0.01181.

[21] μ =221.636, σ = 20.504, p =

0.5704.

[22] μ = 47.417,

σ = 2.731, p = 0.8941.

[23] μ = 47.417,

σ = 2.731, p = 0.1721.

[24] μ = 48.365,

σ = 3.022, p = 0.0654

[11] David Mayhew (1974) Congress: The

Electoral Connection, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

[12] Where: μ = -28.200 and σ

= 24.563

[13] FiveThirtyEight (2022) ‘2022 Election

Forecast – House’. FiveThirtyEight. https://projects.fivethirtyeig

ht.com/2022-election-forecast/house/ [Accessed 8th November

2022].

[14] All electoral statistics for The House

of Representatives taken from: Office of The Historian of The US House of

Representatives (2022) ‘Election Statistics: 1920 to the Present’. History,

Art and Archives: US House of Representatives. https://history.house.gov/Institution/Election-Statistics/Election-Statistics/

[Accessed 8th November 2022].

[15] μ = 93.91, σ = 3.6084, p = 0.1405.

[16] μ = 93.91, σ = 3.6084, p = 0.0092.

[17] μ = 93.91, σ = 3.6084, p = 0.5866.

[18] OpenSecrets (2022) ‘Re-election Rates Over

the Years’. OpenSecrets. https://www.opensecrets.org/elections-overview/reelection-rates [Accessed 8th November 2022].

[2] For more on Judicial Activism, see:

Mark Tushnet (2020) Taking Back The Constitution: Activist Judges and The

Next Age of American Law. Yale: Yale University Press, especially pp. 113-188.

[3] Adam Liptak and Jason Kao (June 30th

2022) ‘The Major Supreme Court Decisions in 2022’. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/06/21/us/major-supreme-court-cases-2022.

[Accessed 8th November 2022].

[4] See, for instance: James Madison (2012)

“Essay 51: James Madison, February 6th 1788”. In Alexander Hamilton,

James Madison and John Jay, Richard Beeman (Ed.), The Federalist Papers.

London: Penguin Books. pp. 92-99.

[6] David R. Mayhew (1991) Divided We

Govern: Party Control, Law Making and Investigations. New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press.

[7] David McKay (2002) “Divided Governance:

Does it Matter?”. In David McKay, David Houghton and Andrew Wroe (Eds.), Controversies

in American Politics and Society. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, pp.

9-19, p. 15.

[8] George C. Edwards , Andrew Barrett and

Jeffrey Peake (1997) ‘The Legislative Impact of Divided Government’. American

Journal of Political Science, 41(2), 545–563. pp. 561-562.

[9] Drew Desilver (March 10th

2022) ‘The polarization in today’s Congress has roots that go back decades’. Pew

Research Centre. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/03/10/the-polarization-in-todays-congress-has-roots-that-go-back-decades/

[Accessed 8th November 2022].

[10] CNN (November 8th 2022) ‘ Kevin

McCarthy asked about impeaching Biden if GOP wins House. Hear his answer’. CNN

Politics. https://edition.cnn.com/videos/politics/2022/11/07/kevin-mccarthy-gop-investigations-marjorie-taylor-greene-cnntm-zanona-sot-vpx.cnn

[Accessed 8th November 2022].

[1] Data taken from: Michael P. McDonald

(2022) ‘National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present’. US

Elections Project. https://www.electproject.org/national-1789-present [Accessed

28th October 2022].